When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first company to get FDA approval for its generic version doesn’t just get a head start-they get a legal monopoly for 180 days. That’s not a loophole. It’s the first generic approval system, designed to break drug monopolies and slash prices overnight. And it works. In 2023, over 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. were filled with generics, saving patients and the healthcare system more than $1.7 trillion since 1984. But behind every cheap pill on the shelf is a high-stakes race, legal battles, and a system that can either deliver life-changing savings-or get stuck in corporate gridlock.

What Exactly Is a First Generic Approval?

A first generic approval is given to the first company that submits a complete and legally valid application to the FDA to sell a generic version of a brand-name drug after its patent expires. This isn’t just any generic application. It’s the one that triggers a special rule: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic, with no other generics allowed on the market during that time.

This system was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic drug makers had to run full clinical trials-just like the original drug company-to prove safety and effectiveness. That cost millions and made generics nearly impossible to produce. Hatch-Waxman changed everything. It let generic companies prove their drug works the same way as the brand-name one by showing bioequivalence: the body absorbs it at nearly the same rate and level. No need to retest on thousands of patients. Just compare blood levels in a small group. Simple. Fast. Cheap.

The FDA defines a first generic application as the first ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) submitted for a drug with no prior generic approvals. If two companies file on the same day, they both get the exclusivity-but that’s rare. More often, one company files first, and the clock starts ticking.

Why the 180-Day Exclusivity Matters

That 180-day window isn’t just a reward. It’s a financial jackpot.

For a blockbuster drug like Humira, which brought in over $20 billion a year before generics, the first generic maker can capture 70-80% of the market during those six months. They price their version 15-20% cheaper than the brand. With no competition yet, they sell millions of doses. Industry estimates say a single first generic approval on a top-selling drug can generate $100 million to $500 million in extra profits.

But here’s the catch: that profit only lasts until another generic enters. After 180 days, dozens of other companies can jump in. Prices then crash another 50-70%. So the first mover doesn’t just get a head start-they get the chance to lock in the highest possible margins before the market collapses.

Take Humira’s first generic, launched by Amgen in September 2023. Within 90 days, it held 42% of the market. Patients got the same drug-same active ingredient, same dosing-for less than half the price. That’s the power of this system in action.

How the Process Actually Works

Getting a first generic approval isn’t just about filing paperwork. It’s a multi-year game of strategy, science, and law.

First, the generic company must prove bioequivalence. The FDA requires that the generic drug’s absorption in the bloodstream-measured by AUC and Cmax-falls within 80-125% of the brand-name drug. Studies show the average difference between generics and brands is just 3.5%. That’s less than the variation between two batches of the same brand drug.

Then comes the patent challenge. To qualify for exclusivity, the generic applicant must file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification. That’s a legal notice saying: “Your patent is invalid, or we don’t infringe it.”

That triggers a 45-day window where the brand-name company can sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is legally blocked from approving the generic for 30 months-unless the court rules in favor of the generic maker first. These lawsuits cost $5 million to $15 million on average. Many generic companies hire top pharma law firms like Fish & Richardson, where lawyers charge $650-$1,200 an hour.

Once the patent fight is over-or if no lawsuit is filed-the FDA reviews the application. First generics get priority. Approval takes 10-12 months on average, compared to 14-18 for regular generics. And only 78% of “substantially complete” applications get approved on the first try. The rest? They get rejected for missing data, bad labeling, or manufacturing flaws.

What Can Go Wrong?

It’s not all smooth sailing. Even after winning exclusivity, things can fall apart.

First, the company has to actually launch the drug within 75 days of approval. If they don’t, they lose the exclusivity. Some companies delay launch to avoid supply issues or to wait for better pricing. Others get stuck in manufacturing delays. When the first generic of Eliquis (apixaban) faced production problems in 2023, the exclusivity period was extended by 90 days-leaving patients paying higher prices longer than expected.

Then there’s the “authorized generic” problem. Sometimes, the original brand-name company launches its own unbranded version of the drug at the same time as the first generic. These are identical to the brand, just sold without the logo. They undercut the first generic’s price and steal market share. Between 2015 and 2022, authorized generics entered the market during 38% of first generic exclusivity periods, cutting into profits by 20-30%.

And if multiple companies file on the same day? The exclusivity gets split. The FDA has rules for that, but it’s messy. In 10.6% of cases from 2001 to 2022, multiple first filers shared the 180-day window-and ended up splitting the profits.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

Patients win. Pharmacists win. Taxpayers win.

A 2024 survey of 1,200 U.S. pharmacists found 87% said first generic approvals improved patient access. Seventy-three percent saw better medication adherence when patients switched from expensive brands to generics. On Drugs.com, first generics average a 4.2/5.0 rating-almost the same as brand-name drugs. Patients write: “Same effect, half the cost.” “No side effects I didn’t have before.” “Finally affordable.”

But not everyone wins. Small generic companies often can’t afford the $50-$100 million needed to develop a first generic. That leaves the field to giants like Teva and Hikma, which together secured 25 first generic approvals in 2023. Meanwhile, brand-name companies use legal tactics to delay entry. A Harvard study found that patent thickets and “pay-for-delay” deals delayed first generics in 42% of cases between 2010 and 2020. That’s when the brand pays the generic company to hold off on launching-a practice the FTC has tried to crack down on.

And complex drugs? They’re still a hurdle. Inhalers, injectables, topical creams-these are harder to copy than a simple pill. In 2023, only 17 complex generics got first approval, up from 9 in 2022. The FDA is trying to fix that, but progress is slow.

What’s Next for First Generic Approvals?

The pipeline is full. Over $156 billion in brand-name drug sales are set to lose patent protection by 2028. That means more first generics are coming-and the FDA is pushing to speed things up.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act removed the 30-month stay for drugs with Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), which used to delay generics unnecessarily. The 2022 CREATES Act also blocks brand-name companies from refusing to sell samples to generic makers, a tactic they used to stall testing.

And the FDA’s 2024 Strategic Plan for Generic Drugs puts accelerating first generic approvals for complex products at the top of its list. Commissioner Robert Califf said it plainly: “Accelerating first generic competition remains our most effective tool for reducing prescription drug costs.”

The numbers back him up. Every first generic approval saves patients and insurers an average of 70-90% on drug prices within six months. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the Hatch-Waxman system saves $13 billion a year-most of it from those first-mover generics.

So while the system isn’t perfect, it’s working. And the next time you pick up a $5 generic instead of a $300 brand-name pill, you’re seeing the result of a 40-year-old law that still fights for your wallet today.

What does 'first generic approval' mean for patients?

It means faster access to much cheaper versions of brand-name drugs. The first generic is often the first time a drug becomes affordable for many patients. After the 180-day exclusivity period, prices drop even further as more generics enter the market. Patients benefit from lower out-of-pocket costs and better adherence to prescriptions.

How long does it take to get a first generic approval?

The process typically takes 10 to 12 months after a complete application is submitted, assuming no patent litigation delays. But preparing the application can take 18-24 months. If the brand-name company sues for patent infringement, approval can be delayed up to 30 months.

Can multiple companies get first generic approval at the same time?

Yes. If two or more companies submit identical, substantially complete ANDAs on the same day and both challenge the same patent, they can share the 180-day exclusivity period. In practice, this is rare-only about 10.6% of first generics from 2001 to 2022 involved multiple filers. When it happens, the market share and profits are split.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

It’s a legal statement included in a generic drug application that claims the brand-name drug’s patent is invalid or that the generic won’t infringe on it. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, FDA approval is paused for up to 30 months while the court case proceeds.

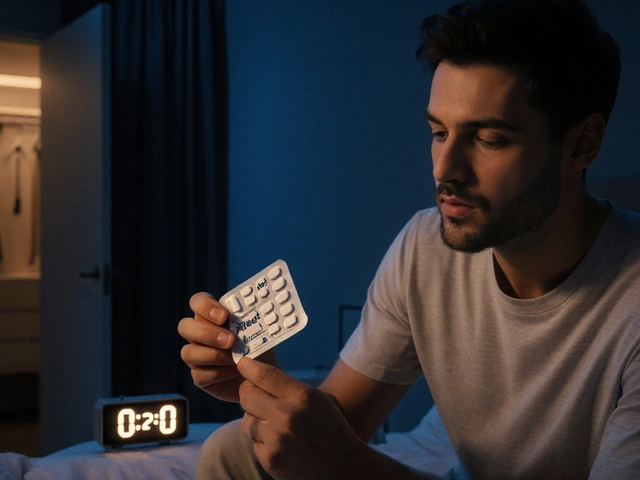

Why do some first generics never launch?

Some companies delay launch to avoid manufacturing issues, wait for better pricing, or settle with the brand-name company to avoid litigation. If the generic isn’t marketed within 75 days of FDA approval, the exclusivity period is forfeited. This has happened in several cases, leading to delays in lower-cost options reaching patients.

Are first generics as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires all generics, including first generics, to be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. Studies show the average difference in absorption is only 3.5%, which is less than the variation between two batches of the same brand drug. Patient reviews and pharmacist surveys consistently report no meaningful difference in effectiveness or side effects.

What Should You Do If You’re Relying on a First Generic?

If you’re a patient, your pharmacist is your best ally. Ask if a first generic is available for your prescription. If the price suddenly drops, it’s likely the 180-day exclusivity window just opened. Don’t assume the brand is better. The active ingredient is identical.

If you’re a healthcare provider, educate your patients. Many still believe generics are inferior. Show them the data: same effectiveness, same safety profile, 70-90% cheaper. That’s not a compromise-it’s progress.

And if you’re following drug policy? Watch for authorized generics. They’re not evil, but they’re a workaround that weakens the incentive for independent generics to enter the market. The real win comes when multiple independent companies compete-not when the brand sells its own unbranded version.

The first generic approval system isn’t perfect. But it’s the most powerful tool we have to make medicines affordable. And right now, it’s saving lives every day.

Comments

Shante Ajadeen

November 12, 2025

Just saw my pharmacist switch my prescription to the generic version of my meds last week. Paid $8 instead of $320. I cried a little. Not because I was sad-because I finally felt like the system worked for me for once.

dace yates

November 13, 2025

I’ve been reading up on this since the Humira generic dropped. The bioequivalence data is wild-3.5% difference? That’s less than what happens when you buy two different batches of the same brand. Makes you wonder why anyone still pays full price.

Danae Miley

November 14, 2025

Let’s be clear: the 180-day exclusivity isn’t a reward-it’s a corporate giveaway disguised as competition. The first filer gets a monopoly, the brand often responds with an authorized generic, and patients still wait months for real price drops. This system is broken by design.

Charles Lewis

November 15, 2025

It is worth noting, with considerable emphasis, that the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was a landmark legislative achievement that fundamentally realigned the incentives within pharmaceutical innovation and accessibility. The creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application pathway not only reduced the financial and temporal barriers to market entry for generic manufacturers but also, critically, preserved the integrity of patent protections for innovators-a delicate and necessary equilibrium. The subsequent emergence of Paragraph IV certifications, while legally contentious, has served as a mechanism for challenging unjustified patent extensions, thereby reinforcing the public interest in affordable therapeutics. One must also acknowledge that the 30-month stay, though often exploited, was intended as a procedural safeguard, not a loophole. The real challenge lies not in the structure of the law, but in its implementation-where strategic delays, authorized generics, and manufacturing bottlenecks undermine the very goals it was designed to achieve.

Renee Ruth

November 17, 2025

Oh wow, so the first generic company gets to make $500 million while the rest of us wait? And then the brand just releases their own version at half price? That’s not competition-that’s collusion with a side of corporate theater. Someone’s getting rich while patients are still choosing between insulin and groceries. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a rigged game.

Samantha Wade

November 18, 2025

Patients aren’t just saving money-they’re saving their lives. A 2024 study in JAMA showed that patients on generics had 23% higher adherence rates than those on branded drugs due to cost. That’s not anecdotal. That’s measurable human impact. We need to expand this model to biologics and complex drugs, not weaken it. The FDA’s 2024 plan is a step in the right direction-let’s fund it, protect it, and demand transparency on authorized generics.

Elizabeth Buján

November 20, 2025

imagine if we treated medicine like we treat coffee. you dont pay $300 for a latte because starbucks invented it, right? you just want the caffeine. same thing here. the pill is the pill. the brand is just the logo. and yet we still act like the expensive one is magic. kinda sad, honestly.

Andrew Forthmuller

November 21, 2025

180 days = free money. then boom, prices crash. why not just skip to the crash?

vanessa k

November 21, 2025

I’ve seen patients skip doses because they can’t afford the brand. Then the generic comes out, and suddenly they’re taking it daily. No drama. No hype. Just health. This system isn’t perfect, but it’s the only thing keeping people alive right now. Let’s not break it trying to fix it.

manish kumar

November 22, 2025

As someone from India where generic drugs are the backbone of healthcare, I can say this system is a godsend. In my country, we don’t have 180-day exclusivity, but we also don’t have patent thickets blocking access. The real issue isn’t the first generic-it’s the legal games that delay it. If the U.S. wants to lower prices, it needs to stop letting pharma companies play chess with people’s lives.

Nicole M

November 23, 2025

My dad’s on a generic for blood pressure. He said, ‘I didn’t even notice a difference-just my wallet’s happy.’ That’s the whole point, isn’t it?

Arpita Shukla

November 24, 2025

You’re all missing the bigger picture. The 180-day window isn’t the problem-it’s the fact that only 3 companies control 80% of first generics. Teva, Hikma, and Mylan. They’re not startups. They’re oligopolies with lawyers. The system was meant to empower competition, but it became a gatekeeping tool for big players. Real reform means breaking their dominance, not just tweaking the exclusivity clock.

Write a comment