Most people don’t know their thyroid is quietly affecting their heart-until something goes wrong. Subclinical hyperthyroidism isn’t a flashy diagnosis. No weight loss, no shaking hands, no sweating through meetings. It shows up on a routine blood test: TSH is low, but T3 and T4? Still normal. And yet, for older adults, especially those over 65, this quiet imbalance can be a ticking time bomb for the heart.

What Exactly Is Subclinical Hyperthyroidism?

It’s not full-blown hyperthyroidism. You don’t feel it. But your thyroid is still overactive-just not enough to push hormone levels out of the normal range. The key marker? Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), made by the pituitary gland to tell your thyroid when to slow down. When TSH drops below 0.45 mIU/L and stays there, while free T4 and T3 stay normal, that’s subclinical hyperthyroidism.

This isn’t rare. About 4 to 8% of the general population has it. But in people over 75? That number jumps to 15.4%. Most cases come from two sources: either a toxic nodular goiter (one or more overactive lumps in the thyroid) or too much thyroid hormone medication-often from over-treatment of hypothyroidism. The problem? It slips under the radar. No symptoms. No panic. Just a lab report.

Why Your Heart Is at Risk

Your heart doesn’t need extra thyroid hormone. It doesn’t ask for it. But when TSH is suppressed-especially below 0.1 mIU/L-it doesn’t matter if your T3 and T4 are technically normal. The heart still feels the strain.

Studies tracking over 25,000 people for 10 years found that those with TSH under 0.1 mIU/L had almost double the risk of heart failure compared to people with normal thyroid function. The risk? Hazard ratio of 1.94. That’s not a small number. For atrial fibrillation-the most common heart rhythm problem in older adults-the risk jumps even higher. One study showed a 2.5-fold increase in AFib when TSH was below 0.1. Even in the milder range (TSH 0.1-0.44), the risk still rose by 63%.

It’s not just rhythm. The heart muscle thickens. The left ventricle gets stiffer. Diastolic function-how well the heart fills with blood between beats-gets worse. Heart rate variability drops, meaning your heart loses its natural flexibility. Sympathetic tone goes up. Vagal tone goes down. In plain terms? Your heart is stuck in “fight or flight” mode, even when you’re sitting still.

And it gets worse with age. A 2013 review in Cardiovascular Research found that people over 60 with subclinical hyperthyroidism had a tripled risk of atrial fibrillation over 10 years. That’s not a coincidence. That’s a pattern.

Bones, Brains, and Beyond

It’s not just the heart. Low TSH also hits your bones. When TSH drops below 0.1, bone turnover speeds up. Bone mineral density drops. One study showed a hazard ratio of 2.3 for fractures-meaning nearly double the risk of breaking a hip or wrist. For older women, especially those with osteoporosis, this is serious.

Cognitive effects are less clear, but emerging data suggests subtle declines in executive function-things like planning, focus, and decision-making-in elderly patients with persistent low TSH. Quality of life usually stays fine unless the heart starts acting up. That’s why symptoms alone can’t guide treatment. You need the numbers.

When Should You Treat It?

This is where it gets messy. Not everyone with low TSH needs treatment. But some definitely do.

The guidelines are clear on thresholds:

- TSH below 0.1 mIU/L: Treatment is strongly considered, especially if you’re over 65, have heart disease, high blood pressure, or osteoporosis.

- TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L: Treat only if you have symptoms, heart rhythm issues, bone loss, or are at high risk for heart disease.

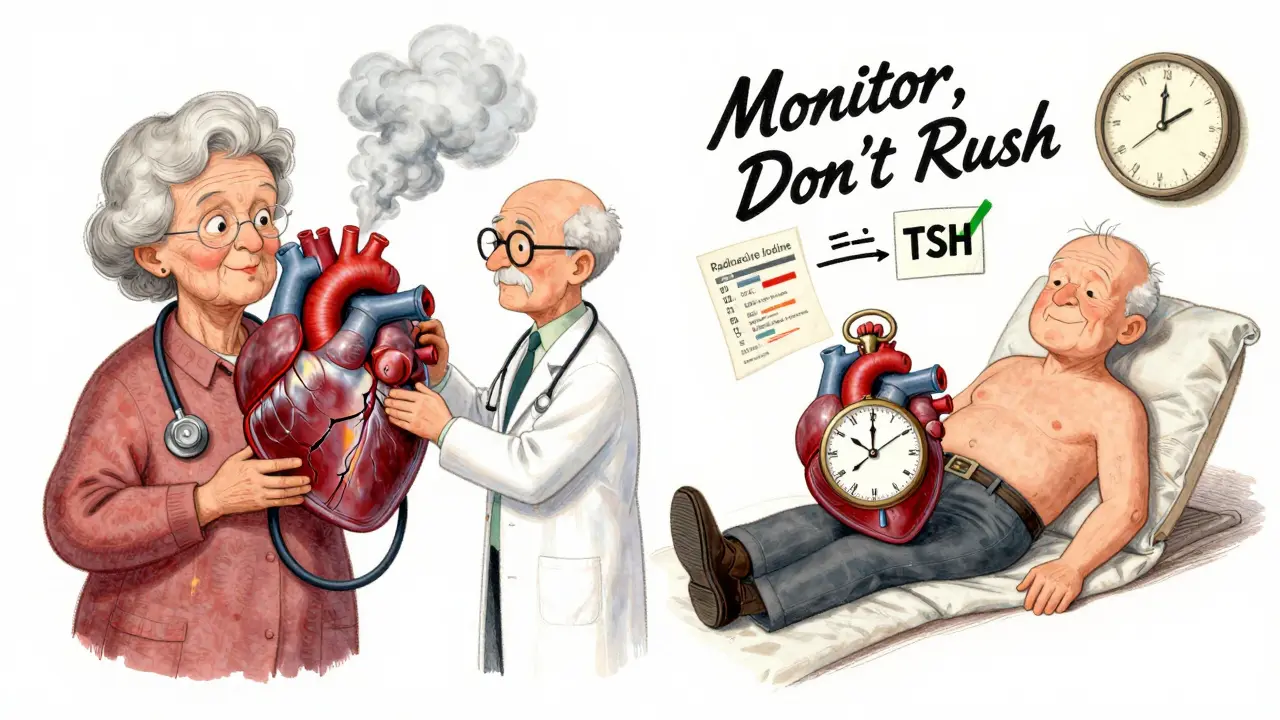

For people with toxic nodules or Graves’ disease (endogenous causes), treatment options include radioactive iodine or surgery. For those on too much levothyroxine (exogenous cause), the fix is simple: lower the dose. But don’t rush. Dropping the dose too fast can swing you into hypothyroidism-and that has its own heart risks.

Beta-blockers like metoprolol or atenolol are often used as a first step. They don’t fix the thyroid, but they calm the heart. They lower heart rate, reduce palpitations, and can even help reverse some of the thickening in the left ventricle. But they’re a band-aid, not a cure.

Dr. Anne R. Cappola, whose research helped shape current thinking, says: “If TSH is below 0.1, treat-even if the patient feels fine.” The evidence is too strong to ignore. The European Thyroid Association agrees. But American guidelines are more cautious. Why? Because overtreatment can backfire.

The Double-Edged Sword of Treatment

Therapy isn’t risk-free. If you ablate the thyroid with radioactive iodine or remove it surgically, you’ll likely become hypothyroid. And hypothyroidism? It raises LDL cholesterol, increases arterial stiffness, and can worsen heart failure. Dr. Kenneth D. Burman warns: “The risks of creating iatrogenic hypothyroidism must be carefully weighed.”

That’s why treatment decisions aren’t one-size-fits-all. A 72-year-old woman with a history of heart attack and TSH of 0.08? She likely benefits from treatment. A 68-year-old man with no heart disease, normal bone density, and TSH of 0.35? Maybe just monitor.

Monitoring frequency matters too:

- TSH below 0.1: Check every 3-6 months.

- TSH between 0.1 and 0.44, no risk factors: Check once a year.

And don’t rely on one test. TSH can dip temporarily due to stress, illness, or medication changes. Repeat it. Confirm it. Don’t treat based on a single abnormal result.

What’s Coming Next?

Research is moving fast. The DEPOSIT study-tracking 5,000 older adults across Europe-is wrapping up in 2026. It might finally answer whether treating mild TSH suppression improves survival. The THAMES trial in the U.S. is looking at whether treating patients with TSH under 0.1 reduces heart attacks and strokes.

For now, the message is simple: low TSH isn’t harmless. Especially in older adults, it’s a silent signal that your heart is under strain. Don’t ignore it. But don’t rush to treat it either. Work with your doctor. Get the numbers right. Monitor regularly. And remember-sometimes the best treatment is not doing anything… yet.

Can subclinical hyperthyroidism cause atrial fibrillation?

Yes. Multiple large studies show a clear link. When TSH drops below 0.1 mIU/L, the risk of atrial fibrillation increases by more than two and a half times. Even in the milder range (0.1-0.44 mIU/L), the risk goes up by 63%. This is especially true in people over 60. Atrial fibrillation isn’t just an annoyance-it raises stroke risk and can lead to heart failure.

Should everyone with low TSH be treated?

No. Treatment isn’t automatic. Guidelines recommend treatment only for TSH below 0.1 mIU/L, especially in people over 65 or those with heart disease, osteoporosis, or symptoms. For TSH between 0.1 and 0.44, treatment is usually reserved for those with clear signs of heart strain or bone loss. Many people with mild suppression never need treatment-just regular monitoring.

Is subclinical hyperthyroidism dangerous if you feel fine?

Yes, even if you feel fine. This condition is called "subclinical" because it doesn’t cause obvious symptoms. But damage to the heart and bones can still happen silently. By the time symptoms like palpitations or fatigue appear, the changes may already be advanced. That’s why blood tests and regular check-ups are critical, especially after age 60.

Can beta-blockers cure subclinical hyperthyroidism?

No. Beta-blockers like metoprolol only manage symptoms-they don’t fix the thyroid. They help lower heart rate, reduce palpitations, and improve heart function temporarily. But they don’t change TSH levels or stop the thyroid from overworking. They’re a bridge, not a solution. The real fix is adjusting medication or treating the root cause-like a toxic nodule.

How often should TSH be checked if you have subclinical hyperthyroidism?

For TSH below 0.1 mIU/L, check every 3 to 6 months. For TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L with no heart or bone issues, once a year is enough. Always repeat abnormal results before making decisions. TSH can dip temporarily due to illness, stress, or medication changes. Confirmation over time is key.