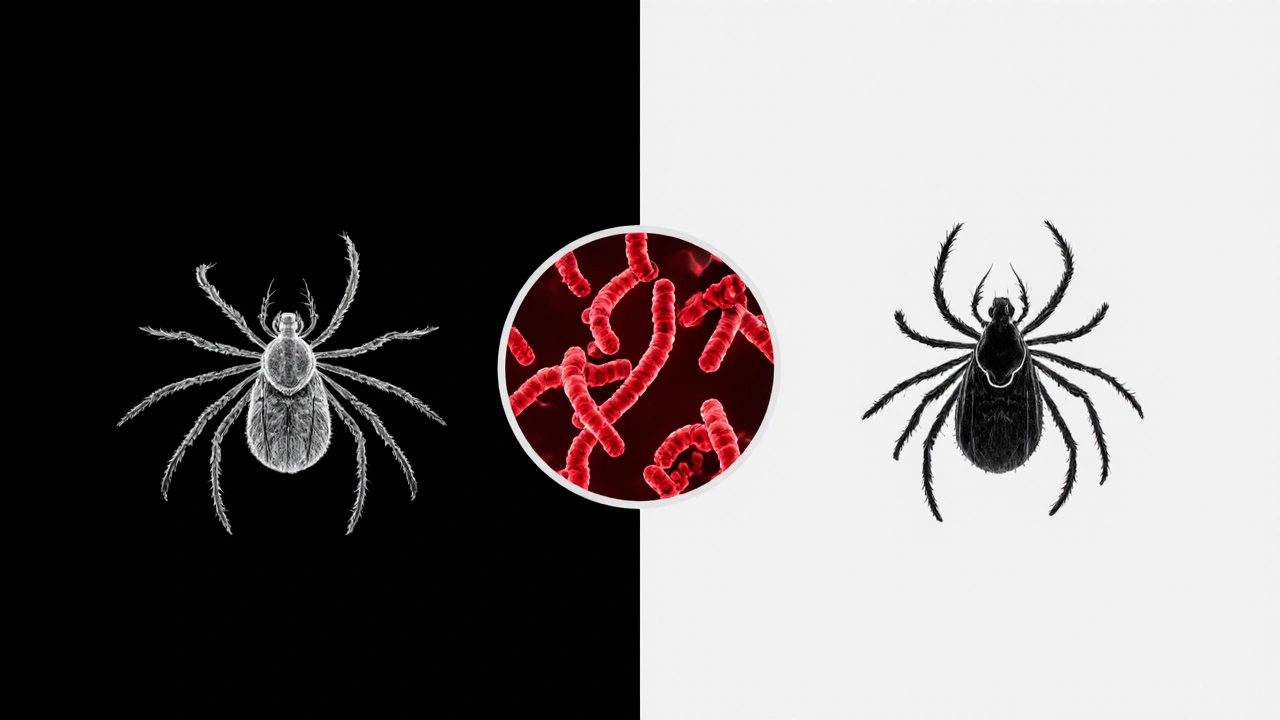

When you hear a buzzing sound in the woods, the first thing that comes to mind is probably a mosquito. But for anyone who’s found a tiny, hard‑shelled tick clinging to skin, the thoughts shift to fever, rashes, and a whole list of possible illnesses. Two names surface most often: Lyme disease and tick fever. Though they sound like separate monsters, they share the same culprits - bacteria carried by ticks - and can even show up together in the same patient.

Key Takeaways

- Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted mainly by the black‑legged tick (Ixodes scapularis).

- Tick fever, often referring to tick‑borne relapsing fever, is caused by Borrelia hermsii and spread by soft ticks like Ornithodoros hermsi.

- Both illnesses can start with fever, headache, and fatigue, but Lyme disease typically adds a distinctive “bull’s‑eye” rash.

- Co‑infection is possible when a single tick carries both bacteria; this can make symptoms more severe and complicate treatment.

- Early diagnosis and a short course of doxycycline usually clear both infections, but prompt medical attention is crucial.

What Is Tick Fever?

“Tick fever” is a shorthand for several tick‑borne illnesses that cause fever. The most common reference is tick‑borne relapsing fever (TBRF). TBRF is caused by spirochetes of the genus Borrelia, primarily Borrelia hermsii. Unlike the hard‑tick bite that introduces Lyme disease, TBRF is transmitted by soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros, which feed quickly-often in less than a minute-while the host sleeps.

Symptoms appear 5‑14 days after a bite and come in waves: high fever, chills, muscle aches, and a pounding headache. After a fever spike, the body may experience a brief lull, only for another wave to follow. This “relapsing” pattern is the disease’s namesake and can last weeks if untreated.

What Is Lyme Disease?

Lyme disease is the most prevalent tick‑borne disease in North America and Europe. It’s caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete that thrives in the midgut of the black‑legged tick (Ixodes scapularis in the U.S., Ixodes ricinus in Europe). The tick must stay attached for at least 36‑48 hours for transmission to occur.

Early Lyme disease often presents with a red, expanding rash called erythema migrans, sometimes with a bull’s‑eye appearance. Flu‑like symptoms-fever, fatigue, headache, and joint pain-may accompany the rash. If not treated, the infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system.

How Ticks Transfer Both Pathogens

Although different tick species usually carry different Borrelia species, there are geographic overlaps. In the western United States, for example, the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) can host both Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii. When a single tick harbors multiple bacteria, a bite may inoculate the host with both, creating a co‑infection scenario.

Co‑infection doesn’t just add up the symptoms; it can amplify them. Patients often report more intense fever, prolonged fatigue, and a higher likelihood of neurological issues. The immune system’s response to one pathogen can inadvertently help the other survive, making diagnosis trickier.

Shared Symptoms and Key Differences

| Feature | Lyme Disease | Tick‑Borne Relapsing Fever |

|---|---|---|

| Causative Agent | Borrelia burgdorferi | Borrelia hermsii |

| Primary Tick Vector | Ixodes scapularis (hard tick) | Ornithodoros hermsi (soft tick) |

| Incubation Period | 3‑30 days | 5‑14 days |

| Typical Rash | Erythema migrans (bull’s‑eye) | Usually absent |

| Fever Pattern | Continuous or intermittent low‑grade | High‑grade relapsing spikes |

| Diagnostic Test | ELISA followed by Western blot; PCR | Spiral‑shaped spirochetes on thick‑blood‑smear; PCR |

| First‑Line Antibiotic | Doxycycline 100mg BID 2‑3weeks | Doxycycline or tetracycline 7‑10days |

Notice how the rash is a major clue for Lyme disease but is largely missing in tick‑borne relapsing fever. That’s why doctors often rely on a detailed travel and exposure history to differentiate the two.

Co‑Infection Risks and Why They Matter

When a tick carries both Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii, the patient may experience overlapping symptoms. Fever may be higher, the rash may appear alongside relapsing episodes, and neurological signs (like facial palsy) can surface earlier.

Co‑infection also influences treatment decisions. While doxycycline covers both pathogens, clinicians may need to monitor patients longer or adjust dosages if symptoms linger. In rare cases, patients with severe relapsing fever may require intravenous ceftriaxone, especially if central nervous system involvement is suspected.

Diagnosis: Spotting the Connection Early

Because early symptoms mimic flu or common viral infections, many people dismiss a tick bite. Here’s a quick checklist doctors use:

- Confirm a recent tick bite or exposure to endemic areas.

- Inspect for erythema migrans or, in the case of relapsing fever, a pattern of fever spikes.

- Order serologic tests: ELISA and Western blot for Lyme; thick‑blood‑smear or PCR for TBRF.

- Consider co‑infection if symptoms are atypical or unusually severe.

Timely testing is vital. Serology for Lyme may be negative during the first weeks, so clinicians often start empirical doxycycline if the suspicion is high.

Treatment Pathways

Lyme disease is usually cured with a short course of doxycycline, 100mg twice daily for 2‑3 weeks. For children under eight or pregnant women, amoxicillin is preferred. If neurological or cardiac complications arise, intravenous ceftriaxone for 2‑4 weeks may be required.

Tick‑borne relapsing fever also responds well to doxycycline, but the regimen is slightly shorter-often 7‑10 days. In severe cases, especially with central nervous system involvement, hospitalization and IV antibiotics become necessary.

Because both infections share the same first‑line drug, co‑infection rarely needs separate medication. However, monitoring is essential: lingering fatigue or joint pain after treatment may signal post‑treatment Lyme disease syndrome or a relapse of TBRF.

Prevention: Staying Tick‑Smart

Prevention works on two fronts: avoiding tick bites and reducing tick habitats.

- Wear long sleeves and pants when hiking in forested areas; tuck pants into socks.

- Use EPA‑registered repellents containing 20‑30% DEET or picaridin on skin and clothing.

- Perform a tick check within 30 minutes of leaving the outdoors. Prompt removal (using fine‑point tweezers, pulling upward) cuts transmission risk.

- Keep yards trimmed, remove leaf litter, and apply tick‑control treatments to pets.

- If you find a tick attached for more than 24hours, consider a prophylactic dose of doxycycline (200mg single dose) after consulting a healthcare provider.

These steps dramatically lower the odds of both Lyme disease and tick‑borne relapsing fever, and they’re easy to integrate into weekend adventures.

Quick Checklist for Anyone Who’s Been Bitten

- Remove the tick within 24hours using tweezers.

- Note the date, location, and tick type (hard vs. soft).

- Watch for a bull’s‑eye rash, fever spikes, or flu‑like symptoms for up to a month.

- Seek medical care promptly if any symptoms appear.

- Ask your doctor about testing for both Lyme disease and tick‑borne relapsing fever, especially if you live in overlapping endemic zones.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get Lyme disease and tick fever from the same bite?

Yes. Some tick species, especially in the western U.S., can carry both Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii. A single bite may introduce both pathogens, leading to co‑infection.

How long after a bite do symptoms appear?

Lyme disease symptoms usually show up within 3‑30 days, while tick‑borne relapsing fever appears after 5‑14 days. The timing can overlap, so keep an eye out for both patterns.

Is the bull’s‑eye rash ever present in tick fever?

No. Tick‑borne relapsing fever typically does not cause a rash. If you see a red expanding rash, it’s a strong hint toward Lyme disease.

Do I need different antibiotics for each disease?

Both infections respond well to doxycycline, so the same antibiotic usually covers both. Severe cases may require IV ceftriaxone, especially for neurological involvement.

Can pets bring ticks carrying these bacteria into the house?

Pets can carry ticks, but the specific bacteria depend on the tick species. Regular tick checks on dogs and cats, plus topical tick preventatives, reduce the risk of bringing infected ticks indoors.

Is there a vaccine for Lyme disease or tick fever?

A Lyme disease vaccine for humans was withdrawn years ago, and no approved vaccine exists for tick‑borne relapsing fever. Research continues, but prevention remains the best strategy.

Comments

carol messum

October 15, 2025

I’ve always been fascinated by how nature intertwines different illnesses. The idea that a single bite can introduce two separate bacteria makes you think about the hidden complexity of ecosystems. It reminds me that we’re often unaware of the tiny worlds living on us. Keeping an eye on tick prevention feels like a small act of respect toward that complexity.

Jennifer Ramos

October 21, 2025

Exactly, it’s wild how co‑infection can turn a simple rash into a full‑blown fever marathon. The good news is that doxycycline covers both, so treatment stays straightforward 😊. Still, staying vigilant after a hike is the real key.

abhi sharma

October 27, 2025

Ticks are basically nature’s tiny surprise packages, aren’t they?

mas aly

November 2, 2025

True, the surprise can be unpleasant, especially when the symptoms bounce around like a yo‑yo. The quick bite of a soft tick means the infection can start before you even notice. That’s why a thorough tick check right after outdoor activities matters a lot. It’s a simple habit that can save you a lot of trouble.

Abhishek Vora

November 7, 2025

When we speak about tick‑borne diseases, the first name that jumps to mind is often Lyme disease, but the story does not end there. Tick‑borne relapsing fever, caused by Borrelia hermsii, plays an equally important yet less publicized role in the spectrum of tick infections. Both pathogens belong to the same genus, which explains why they sometimes share a vector. In the western United States, the Rocky Mountain wood tick has been documented to harbor both Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii simultaneously. A single bite from such a co‑infected tick can inoculate the host with both organisms, leading to overlapping clinical presentations. Patients may experience the classic bull’s‑eye rash of Lyme disease alongside the high‑grade, relapsing fevers characteristic of TBRF. This dual presentation can confound clinicians, especially when serologic tests return ambiguous results. The standard two‑step testing algorithm for Lyme disease-ELISA followed by Western blot-may miss early infection, while thick‑blood‑smear microscopy for relapsing fever is rarely performed in routine labs. Consequently, empirical treatment with doxycycline is often initiated based on exposure history and symptom pattern. Doxycycline, at 100 mg twice daily, is effective against both Borrelia species and typically clears the infection within two to three weeks. In severe cases involving neurological complications, intravenous ceftriaxone may be required, especially for Lyme neuroborreliosis, while relapsing fever with central nervous system involvement may also necessitate IV therapy. Beyond treatment, prevention remains the cornerstone of public health strategy. Regular use of EPA‑registered repellents, wearing long sleeves, and performing meticulous tick checks after outdoor excursions dramatically reduce the risk of both diseases. Land management practices such as clearing leaf litter and treating pet collars with acaricides further diminish tick habitats. Ultimately, awareness of co‑infection possibilities equips both clinicians and patients to act swiftly, minimizing long‑term sequelae and preserving health.

Terri DeLuca-MacMahon

November 13, 2025

You nailed the details! 🌟 Knowing the full picture helps us all feel more prepared. Let’s keep sharing these tips so everyone can stay safe on the trail. Together we can make outdoor adventures worry‑free! 🙌

Dominique Watson

November 19, 2025

The United States bears a disproportionate burden of tick‑borne illnesses, a reality that underscores our responsibility to lead global research initiatives. While European nations have made progress in vaccine development, our extensive habitats demand robust surveillance and funding. It is imperative that federal agencies allocate sufficient resources to expand tick control programs across endemic regions. Only through decisive action can we safeguard the health of American citizens and set a precedent for international partners.

Maureen Crandall

November 25, 2025

Absolutely agree more funding needed

Andrea Rivarola

December 1, 2025

Having read through the comprehensive overview of both Lyme disease and tick‑borne relapsing fever, I find myself reflecting on the intricate interplay between vector biology, pathogen genetics, clinical presentation, diagnostic challenges, treatment protocols, and preventive measures, all of which converge to form a tapestry of public health considerations that, while daunting, also offers numerous opportunities for education, research, and community engagement, especially when we recognize that simple actions such as regular tick checks, proper clothing, and the use of repellents can dramatically reduce the incidence of these infections, thereby empowering individuals to enjoy outdoor activities with confidence and encouraging policymakers to invest in targeted tick‑control strategies that balance ecological preservation with human health.

Write a comment