Ever wondered why your prescription for a certain medication still costs hundreds of dollars a month, even though it’s been on the market for over a decade? You’d think that after all this time, someone would have made a cheaper version. But for some drugs, there’s still no generic option - not because they’re too new, but because the system is designed to keep them that way.

Patents Aren’t the Whole Story

Most people assume that once a drug’s patent runs out, generics automatically appear. That’s not true. The patent clock starts when the drug is first filed - usually years before it even hits shelves. So by the time a brand-name drug like Lipitor (atorvastatin) hits the market, it’s already been 10-12 years into its 20-year patent life. That leaves maybe 8 years of exclusivity before generics can enter. But even then, they don’t always show up. That’s because patents aren’t the only barrier. Companies file multiple patents - on the active ingredient, the pill coating, the delivery method, even the way it’s packaged. This is called a “patent thicket.” It’s legal, and it’s common. A 2020 Harvard study found that pharmaceutical companies use these overlapping patents to delay generics by an average of 3.2 years beyond the original expiration. For drugs like Nexium (esomeprazole), AstraZeneca kept filing new patents every few years, stretching exclusivity until 2014 - even though the original patent expired in 2001.Some Drugs Just Can’t Be Copied

Not all drugs are made the same. Most are simple chemical compounds - pills you swallow with water. But some are made from biological material, like Premarin, a hormone therapy made from the urine of pregnant mares. It contains a mix of 10+ estrogen compounds, many of which aren’t fully identified. No lab can replicate that exact mix. So even after the patent expired, no generic version was ever approved. The FDA says it can’t prove a copy would work the same way. Then there are biologics - complex drugs made from living cells. Think Humira (adalimumab) or Enbrel (etanercept). These aren’t made by mixing chemicals. They’re grown in bioreactors, like tiny biological factories. Even small changes in temperature, pH, or cell strain can alter the final product. That’s why generics for these drugs aren’t called “generics” at all - they’re called “biosimilars.” And they require 12 years of data exclusivity under U.S. law, plus years of clinical testing. The first biosimilar for Humira didn’t reach the U.S. market until 2023 - seven years after its patent expired.Complex Delivery Systems Block Competition

It’s not just what’s in the pill - it’s how it gets delivered. Take Advair Diskus, an inhaler for asthma. The active ingredients (fluticasone and salmeterol) are simple enough. But the device that delivers them? That’s proprietary. The way the powder is mixed, the airflow dynamics, the way the canister clicks - all of it matters. A generic version would need to match not just the drug, but the entire delivery system. The FDA requires full bioequivalence testing for that. It’s expensive. It’s slow. And many generic makers just walk away. Same goes for extended-release pills like Prozac Weekly. These aren’t just pills that last longer. They use special coatings or matrices to slowly release the drug over days. Change the inactive ingredients even slightly, and the release profile shifts. That could mean the drug doesn’t work as well - or worse, causes side effects. So the FDA demands extra studies. That adds $10 million or more to the cost of bringing a generic to market. For a drug with modest sales, it’s not worth it.

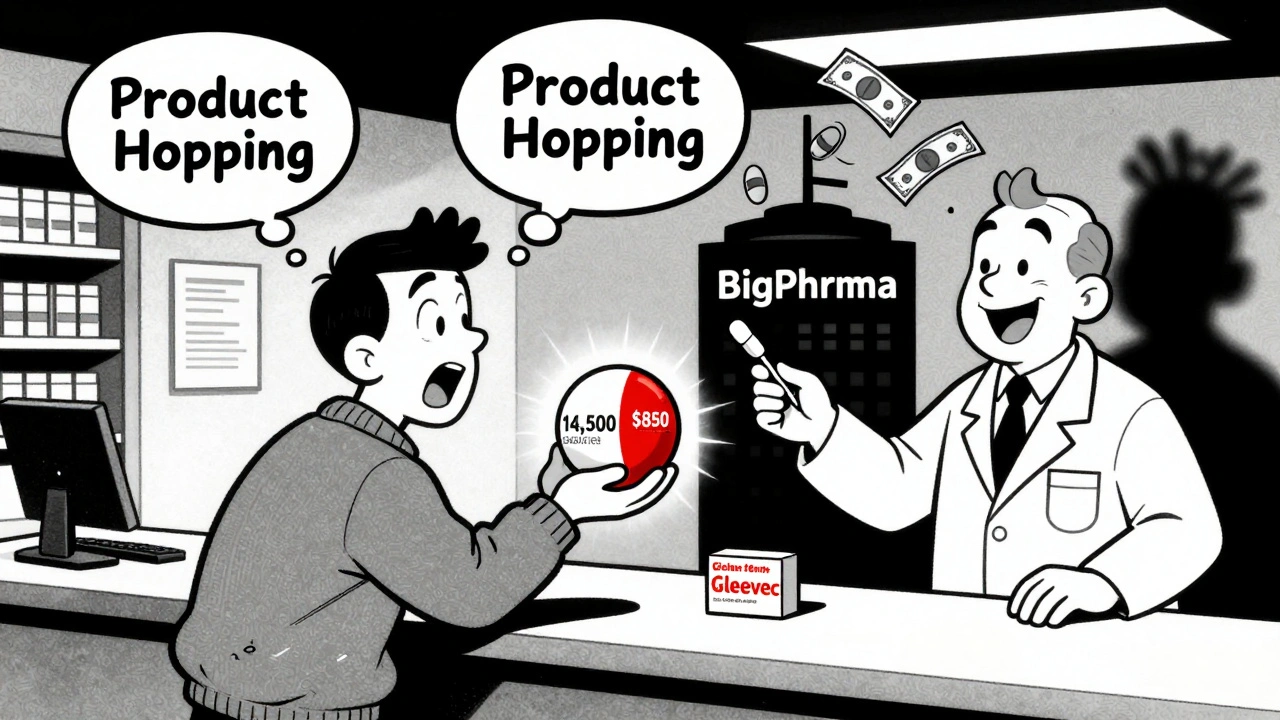

“Product Hopping” Keeps Prices High

Some companies don’t wait for patents to expire. They change the drug before they have to. This is called “product hopping.” Take EpiPen. Mylan held the patent on the original auto-injector design. As expiration neared, they launched a redesigned version - same epinephrine, different plastic casing, different needle mechanism. The FDA approved it as a “new” product. That reset the exclusivity clock. Patients had to switch. Insurance plans had to update formularies. Generics couldn’t enter because the “original” version was no longer on the market. The tactic delayed competition for over a decade. It’s not just EpiPen. Similar moves have been made with Abilify, Daytrana, and others. A 2021 Health Affairs study found that product hopping delays generic entry by 12-18 months per tweak. And because these changes are minor, patients often don’t realize they’ve been moved to a new version - until their copay jumps.Why Generic Makers Walk Away

Even when patents expire, generic companies don’t always jump in. Why? Because the market isn’t always worth the effort. Take a drug that treats a rare condition - say, a pediatric epilepsy syndrome. Only 5,000 people in the U.S. need it. The cost to prove bioequivalence? $15 million. The price per pill? $10. Even if they sold 100% of the market, they’d make $18 million a year. After manufacturing, legal fees, and FDA fees, profit? Maybe $2 million. Not worth it. Then there’s the “pay-for-delay” tactic. Brand-name companies pay generic makers to stay out of the market. The FTC found 297 such deals between 1999 and 2012. In one case, a generic maker was paid $100 million to delay launching a cheaper version of a blood thinner. Those deals cost U.S. consumers an estimated $3.5 billion a year. The CREATES Act of 2019 tried to stop this by forcing brand companies to supply samples to generic makers - but enforcement is still patchy.

What This Means for Patients

The result? You’re paying more. A 2022 GoodRx analysis showed that brand-name drugs with no generic alternatives cost, on average, 437% more than those with generics. For a drug like Gleevec (imatinib), patients paid $14,500 a month before the generic came out. After? $850. That’s a 94% drop. But it’s not just about cost. Some patients report differences with generics - especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. One patient on PatientsLikeMe said the generic version of Spiriva HandiHaler “felt different in my lungs.” That’s not just anecdotal. For drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications, tiny variations in absorption can lead to serious side effects. That’s why some doctors stick with brand names - not because they’re better, but because they’re predictable. Medicare data shows that 22% of patients taking non-generic drugs spend over $5,000 a year out of pocket. For those on fixed incomes, that’s a life-altering burden.Change Is Coming - But Slowly

The FDA is trying. Under its 2022 GDUFA III program, they’ve prioritized reviewing complex generics. In 2022 alone, approvals for these tricky drugs rose 27% compared to 2021. Biosimilars are also growing - from 32 approved in 2022 to an expected 75 by 2025. But experts agree: about 5% of drugs will likely never have true generics. These include ultra-complex biologics, orphan drugs for rare diseases, and those with impossible-to-replicate delivery systems. Insulin, for example, will likely stay brand-dominated until at least 2026. For now, the best advice for patients? Ask your pharmacist. If your drug has no generic, ask if there’s a similar medication that does. A 2021 study showed that when pharmacists helped switch patients off non-generic antidepressants like Viibryd to generics like sertraline, 68% had just as good results - and saved hundreds a month. The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed - for drug companies. But for patients? It’s a gamble. And too often, you’re paying for the house.Why don’t all expired-patent drugs have generic versions?

Not all drugs can be easily copied. Some, like biologics or complex inhalers, require advanced manufacturing techniques that generic companies can’t replicate without massive investment. Others are protected by multiple overlapping patents, or the market is too small to justify the cost. Even when patents expire, companies may delay generics through legal tactics or by changing the drug slightly to reset exclusivity.

What’s the difference between a generic drug and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs - like pills made of one or two compounds. Biosimilars are copies of biologics - large, complex proteins made from living cells. Because biologics can’t be perfectly replicated, biosimilars are “similar but not identical.” They require more testing and are more expensive to produce. The FDA requires 12 years of data exclusivity for biologics before biosimilars can enter the market.

Can a generic drug work differently than the brand name?

By law, generics must be bioequivalent - meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream within 80%-125% of the brand version. For most drugs, this means they work the same. But for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like seizure meds, thyroid hormones, or blood thinners - even small differences can matter. Some patients report feeling different on generics, though studies show most see no change. If you notice a difference, talk to your doctor.

How do pharmaceutical companies delay generic competition?

They use several tactics: filing multiple patents (patent thickets), paying generic makers to delay entry (pay-for-delay), making minor changes to the drug before patent expiration (product hopping), and refusing to supply samples needed for testing. These tactics are legal under current U.S. law, though regulators are cracking down. The CREATES Act now forces companies to provide samples, but enforcement remains inconsistent.

Are there any drugs that will never have generics?

Yes. About 5% of medications - mainly ultra-complex biologics, orphan drugs for rare diseases, and those with proprietary delivery systems - are unlikely to ever have true generics. Examples include certain insulin formulations, some cancer biologics, and drugs made from biological sources like pregnant mare’s urine (Premarin). These are too complex, too expensive to replicate, or too niche to attract generic manufacturers.

Comments

aditya dixit

December 6, 2025

It’s wild how the system is engineered to keep prices high even after patents expire. I’ve seen this with my dad’s diabetes meds-same active ingredient, but the generic was ‘not bioequivalent’ according to the pharmacy. Turns out, the brand just changed the coating slightly. They’re not selling medicine anymore. They’re selling lock-in.

It’s not capitalism. It’s feudalism with lawyers.

And yet, we act surprised when people choose between food and insulin.

Lynette Myles

December 7, 2025

Big Pharma owns the FDA, Congress, and your doctor’s prescription pad. This isn’t a flaw-it’s the business model.

Annie Grajewski

December 8, 2025

so like… if i make a pill that looks like advair but the canister clicks a lil different… is that illegal? or just really really expensive to prove? bc honestly i’d just buy a $30 generic if i could. why does my inhaler cost more than my rent?

also who designed these things? a robot that hates humans?

Jimmy Jude

December 8, 2025

Let me be the first to say this out loud: We are being systematically looted by people who wear suits and say ‘patient outcomes’ while laughing all the way to the Cayman Islands.

There’s no ‘market failure’ here. This is a perfectly functioning extraction engine. The only thing broken is our moral compass.

And don’t get me started on ‘biosimilars.’ That’s just corporate doublespeak for ‘we’ll charge you 80% of the brand price and call it a win.’

Meanwhile, my neighbor’s kid can’t get her seizure meds because the insurance company says ‘we don’t cover that version.’

It’s not healthcare. It’s a casino where the house always wins-and you’re the slot machine.

Mark Ziegenbein

December 9, 2025

Consider the philosophical implications of this system: We live in a society where the ability to heal is commodified to the point that the very molecules designed to restore life are locked behind intellectual property regimes that prioritize shareholder value over biological necessity.

The patent system was never meant to be a perpetual monopoly on human physiology. Yet here we are-where a molecule derived from horse urine is more valuable than the dignity of a child who can’t afford to breathe.

This isn’t innovation. It’s necrocapitalism. We are not treating disease. We are monetizing vulnerability.

And the saddest part? Most people don’t even realize they’re being played. They think the problem is ‘too expensive’ when the real problem is that we’ve normalized the idea that health is a privilege, not a right.

And until we stop treating pharmaceuticals like luxury goods and start treating them like oxygen-we’re not just failing as a society. We’re failing as a species.

Ada Maklagina

December 10, 2025

My pharmacist just told me to switch from Viibryd to sertraline. Saved me $400/month. No difference in how I feel.

Why are we still paying brand prices for old drugs?

Harry Nguyen

December 10, 2025

Other countries are laughing at us. We pay 5x more for the same pills. And we still think we’re the best? Wake up. This isn’t freedom. It’s corporate colonialism.

sean whitfield

December 11, 2025

patents are for inventors not for corporations that buy them and sit on them

if you made it you get 5 years

if you bought it you get nothing

but no one cares because the lobbyists are richer than your grandma's savings

Carole Nkosi

December 11, 2025

They don’t want you healthy. They want you dependent. Every time you refill, they profit. A cure is a business failure. That’s why insulin hasn’t dropped in price in 100 years.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s medical slavery.

Philip Kristy Wijaya

December 13, 2025

One must consider the structural inevitability of rent-seeking behavior in late-stage capitalism. The pharmaceutical industry, as a hegemonic entity, has achieved a state of institutional capture wherein regulatory bodies function not as arbiters of public health but as conduits for shareholder value maximization. The consequence is not incidental-it is systemic. The patient is not a stakeholder. The patient is a revenue stream.

And yet we continue to vote for politicians who accept their campaign donations. The tragedy is not the system. The tragedy is our complicity.

Jennifer Patrician

December 13, 2025

they're hiding behind 'safety' but the real reason is profit

you think the FDA doesn't know how to approve generics? they could do it in months

they're waiting for the right price to be paid

you think that's a coincidence? no

it's a bribe with a white coat

Mellissa Landrum

December 14, 2025

generic = bad

brand = safe

but the brand is the same chemically

so why does it cost 10x?

bc your doctor gets free vacations from the pharma reps

and you pay for it

Mark Curry

December 15, 2025

my wife switched from brand to generic for her thyroid med. no issues. saved $300/mo.

weird how the system makes you feel guilty for wanting to pay less.

maybe we need more pharmacists like hers.

peace.

Write a comment