When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, the market doesn’t just change-it collapses. Prices drop by 80% or more. Sales vanish overnight. And if you’re the company that spent $2 billion developing that drug, you need to know exactly when it’s going to happen. Not when the patent expires on paper. Not when you think it might. But when the first generic pill actually hits pharmacy shelves-and how many more will follow.

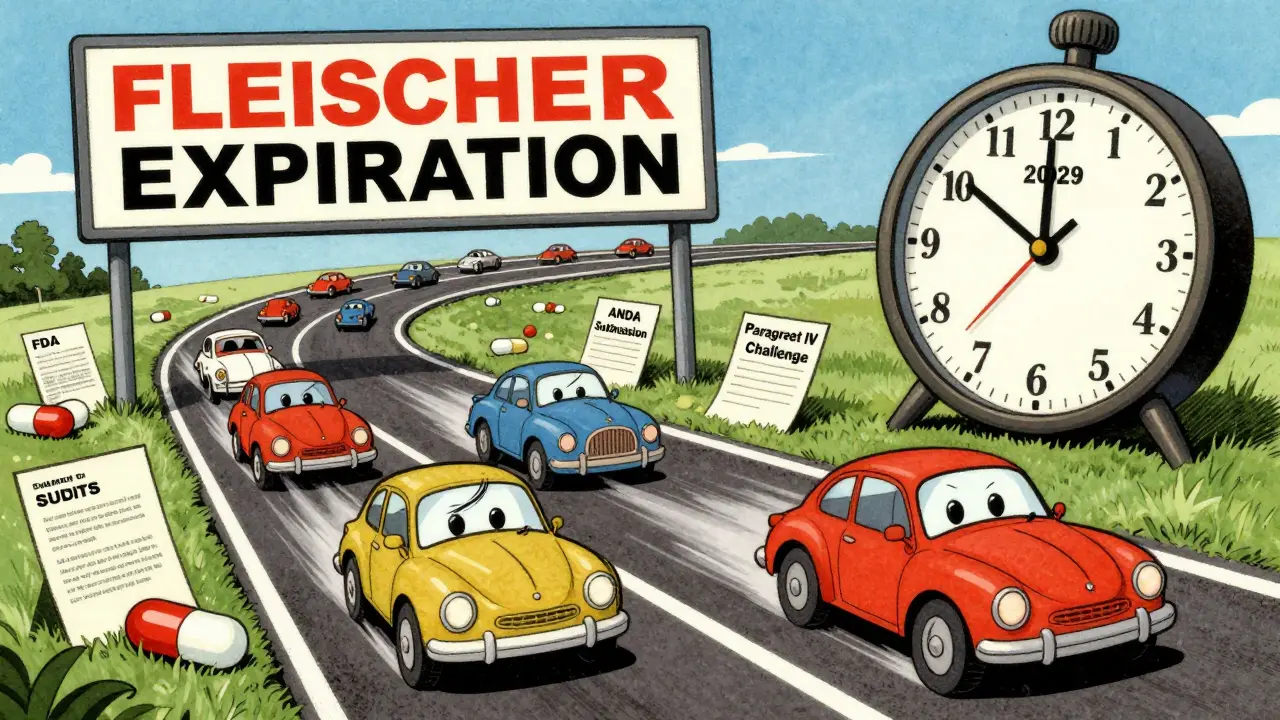

It’s not about the patent date

Most people assume that when a drug’s patent expires, generics flood the market the next day. That’s not how it works. The patent expiration date is just the starting line. The real race begins with the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA)-the paperwork a generic manufacturer files with the FDA to prove their version works the same as the brand. And that process takes years.On average, it takes 38 months from the time an ANDA is submitted to when the FDA approves it. That’s over three years. And that’s only if nothing goes wrong. If another company sues over patent infringement, or if the FDA finds issues with the manufacturing process, that clock can stretch out even longer. In fact, 42% of patent lawsuits delay generic entry by nearly two years. So if your drug’s patent expires in 2027, don’t assume generics will be on shelves in 2027. You might be looking at 2029.

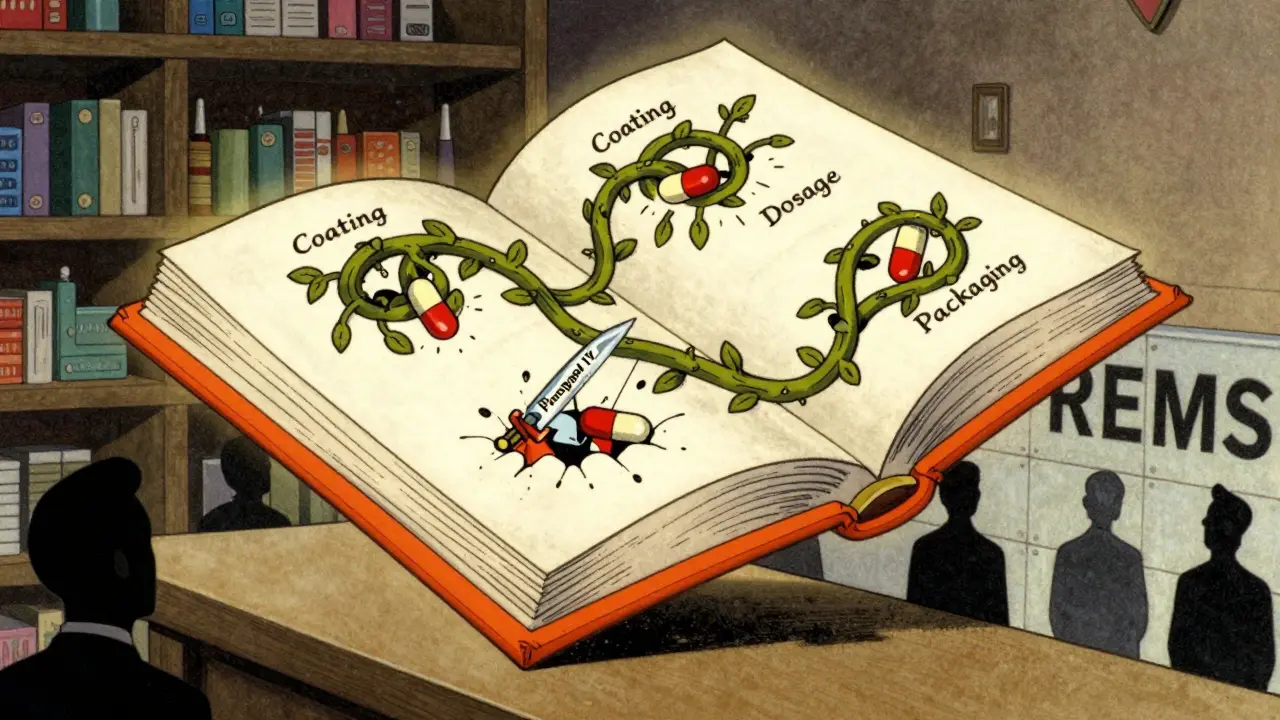

The Orange Book is your bible

The FDA’s Orange Book is the single most important document in this whole game. It lists every patent tied to a brand-name drug, along with any exclusivity periods and whether a generic company has filed a challenge. If you’re not tracking this, you’re flying blind.Each patent listed here isn’t just legal jargon-it’s a potential roadblock. Some companies file dozens of patents on minor changes: a new tablet coating, a slightly different dosage form, even a new packaging design. These are called patent thickets. They’re not meant to protect innovation-they’re meant to delay competition. Take Humira: its core patent expired in 2016, but with over 130 additional patents filed, generic entry didn’t meaningfully begin until 2023.

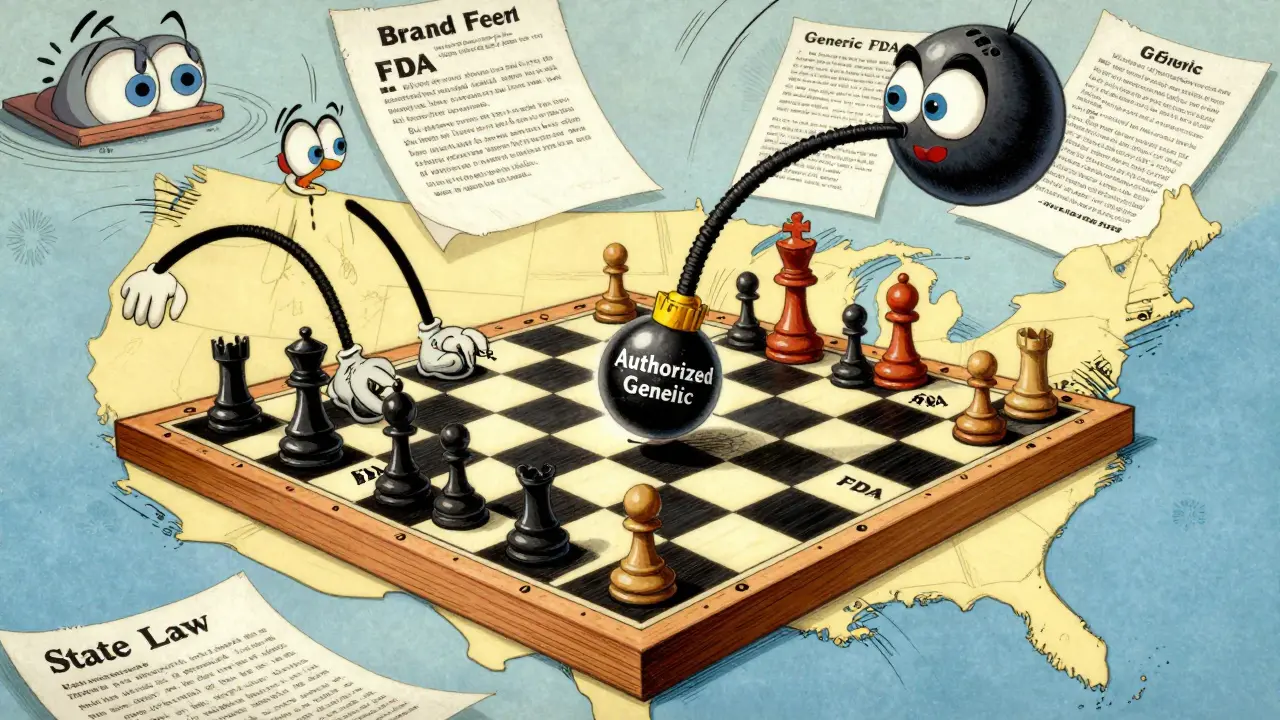

And then there’s the Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an ANDA and says, “We believe this patent is invalid or won’t be infringed,” they’re basically declaring war. That triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for up to 30 months. That’s why 78% of first generic entrants launch during their 180-day exclusivity window-because they know the clock is ticking.

Not all drugs are created equal

Some drugs are easy targets for generics. Others? Not so much. Small-molecule drugs-like pills you swallow-are the low-hanging fruit. They’re chemically simple, and once the patent’s gone, manufacturers can copy them with relative ease. For these, forecasting models are 83% accurate within a year.But biologics? Those are different. They’re made from living cells, not chemicals. Think insulin, rheumatoid arthritis drugs, cancer treatments. The 2010 BPCIA gave them 12 years of data exclusivity, and even after that, biosimilars (the generic version of biologics) take 12-18 months to develop and get approved. And because they’re so complex, the FDA doesn’t consider them “interchangeable” unless they prove they’re nearly identical in every way. That’s why only 38% of eligible biologics have any biosimilar competition, compared to 92% of small-molecule drugs.

Even within small molecules, some drugs are harder to copy. Inhalers, injectables, topical creams-these are called “complex generics.” They require more testing, more precision, and more time. Approval for these can take 52 months, nearly a year longer than standard pills. And if the brand company has a REMS program (a risk management plan that restricts distribution), that adds another 14 months of delay.

Price drops don’t happen all at once

When the first generic hits, prices don’t immediately crash. They fall in stages. The first generic typically reduces the price by 39%. The second competitor pushes it down another 15%, to 54% below brand. By the sixth generic, you’re looking at 85% less than the original price.But here’s the twist: if the brand company launches its own generic-that’s called an authorized generic-it can wipe out the price drop before the real competition even starts. In 41% of cases, this happens. And most forecasting models miss it. They assume the brand will just sit back and watch. They don’t account for the fact that companies like Pfizer and AbbVie have teams dedicated to launching their own generics to protect margins.

And then there’s state laws. California passed a law in 2022 that makes it harder for pharmacists to substitute generics without doctor approval. That slowed price declines by 8.2% compared to other states. In Texas, it’s different. In New York, it’s different again. If your model only uses national averages, you’re wrong.

What breaks the models

Even the most expensive forecasting tools-like Evaluate Pharma’s J+D or IQVIA’s models-get it wrong. Why? Because they can’t predict human behavior.Take “product hopping.” That’s when a company suddenly switches patients from an old drug to a new version just before the patent expires. The new version has a slightly different formulation, maybe a new pill shape or extended-release version. The brand claims it’s better. Patients switch. Pharmacists switch. And suddenly, the old drug’s market shrinks-so even if generics come in, there’s no big revenue left to fight over. This tactic delayed competition in 63% of the top 100 drugs.

Then there’s “pay-for-delay.” That’s when the brand pays a generic company to hold off on launching. It’s illegal in the U.S. now, but it still happens through side deals-like licensing agreements or exclusive distribution rights. These deals aren’t always public, so models don’t see them coming.

And don’t forget the FDA backlog. During the pandemic, approval times stretched by over seven months because staff were stretched thin. Most models still use pre-pandemic timelines. They’re outdated.

Who’s doing this right?

The companies that get it right have teams that aren’t just analysts. They include patent lawyers, regulatory specialists, and even game theory economists. Why economists? Because generic entry isn’t just about timing-it’s about strategy. Who files first? Who waits? Who challenges a patent? Who doesn’t? It’s a chess game.Successful teams start tracking a drug 36 to 48 months before the patent expires. They monitor every patent filing, every court case, every FDA inspection report. They track citizen petitions-those are formal complaints filed by the brand to block a generic. They take 7.1 months on average to delay approval.

And they don’t rely on one tool. They cross-check Drug Patent Watch, Cortellis, and the FDA’s own data. They know that if a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification and the brand doesn’t sue within 45 days, that’s a green light. If the FDA grants a Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) designation, that means the market is underserved-and the first generic gets 180 days of exclusivity. That changes everything.

What’s next?

By 2026, AI is expected to cut prediction errors in half. Machine learning models are now scanning thousands of patent lawsuits, FDA letters, and court transcripts to spot patterns humans miss. They’re learning which companies are likely to sue, which ones are likely to settle, and which patents are weak.But even AI can’t predict everything. It can’t tell you if a doctor will suddenly stop prescribing the brand because of a new guideline. It can’t predict if Medicare will start negotiating prices under the Inflation Reduction Act-which could reduce generic price erosion by 15-20% for certain drugs.

What it can do is give you a better shot. The difference between predicting entry within six months versus 14 months is worth hundreds of millions in revenue. For a company losing $1 billion a year to generics, that’s not just a forecast-it’s survival.

What you need to do now

If you’re managing a brand drug with a patent expiring in the next 3-5 years, here’s your checklist:- Check the FDA Orange Book for every patent and exclusivity period tied to your drug.

- Look for Paragraph IV certifications-those are your early warning signs.

- Track any litigation. If a lawsuit was filed, add 18-30 months to your timeline.

- See if your drug has a REMS program or is a complex generic-that adds time.

- Monitor for authorized generics. Your own company might be the one launching them.

- Check state substitution laws. They vary. And they matter.

- Start planning your lifecycle strategy now. Don’t wait until the patent expires.

There’s no crystal ball. But with the right data, the right team, and the right tools, you can see the storm coming-and prepare for it.

Comments

Brittany Wallace

January 4, 2026

It’s wild how we treat medicine like a stock market instead of a human right. 😔 We’re not just predicting when pills get cheaper-we’re predicting when people can breathe again. The real tragedy? The people who need these drugs the most are the ones who get lost in the spreadsheets.

And yet, we celebrate the ‘strategic’ moves of pharma giants like they’re chess masters instead of gatekeepers. Humira’s 130 patents? That’s not innovation-that’s legal gaslighting.

I wish we had a system that rewarded healing over hoarding.

But hey, at least we’ve got AI now. Maybe it’ll figure out how to value life over profit. 🤷♀️

veronica guillen giles

January 5, 2026

Oh wow, so the pharma companies didn’t just invent drugs-they invented a whole new sport called ‘Patent Dodgeball.’

‘Oh, we changed the pill’s color!’ - *sue!*

‘Oh, we added a coating that lasts 0.2 seconds longer!’ - *sue!*

‘Oh, we renamed it and told doctors it’s ‘better’!’ - *sue, sue, sue!*

And the FDA? Just sitting there like, ‘Y’all are ridiculous but… we’re backed up.’

Meanwhile, my grandma’s insulin co-pay is $400. 😘

Michael Burgess

January 7, 2026

Man, this is the most underrated deep dive I’ve read all year. Seriously. I work in supply chain for a mid-sized pharma firm, and this? This is the stuff we whisper about in the breakroom.

That authorized generic move? Absolute chess. I’ve seen it happen-company launches their own generic at 60% off the brand price the *day* the patent drops. Kills the first entrant before they even get shelf space.

And don’t even get me started on REMS. One client had a topical cream that couldn’t be distributed outside specialty pharmacies. Took 18 months just to get a generic partner approved to handle logistics.

Also-state laws? Huge. California’s substitution rules killed a $200M generic launch last year. No one saw it coming. 🤯

TL;DR: This isn’t science. It’s war. And the battlefield is paperwork.

Hank Pannell

January 8, 2026

The structural asymmetry here is profound: the innovator holds monopolistic power, protected by legal architecture designed to incentivize R&D, yet the system has been weaponized into a mechanism of rent extraction-far beyond its original telos.

Patent thickets function as anti-commons: a proliferation of low-quality, incremental IP claims that collectively erect non-technical barriers to entry, effectively subverting the constitutional purpose of patents-to promote progress.

Moreover, the FDA’s adjudicative capacity is structurally under-resourced, while litigation incentives are asymmetrically skewed toward incumbents. The 30-month stay? A de facto extension of monopoly via judicial delay.

And yet, the market’s response-authorized generics, product hopping, pay-for-delay-reveals not market efficiency, but systemic capture.

AI may optimize prediction, but it cannot resolve the ethical paradox: when innovation becomes indistinguishable from obstruction, who is the system truly serving?

Perhaps the real question isn’t ‘when will generics arrive?’ but ‘why do we tolerate this?’

Ian Ring

January 8, 2026

Interesting. Very interesting. But... I wonder if we're missing the bigger picture?

Yes, the Orange Book is critical. Yes, Paragraph IV filings matter. Yes, REMS delays are a nightmare.

But what about the prescribers? What about the pharmacists? What about the patients themselves?

Many patients-especially elderly ones-are terrified of switching. They’ve been on the brand for 10 years. Their doctor says, ‘Stick with it.’ The pharmacist says, ‘I’ll call your doctor.’

And then there’s marketing. The brand spends millions on detailing, samples, and patient assistance programs.

So even when generics are approved... they don’t get used.

It’s not just about timing. It’s about trust.

And that’s harder to model.

Just saying. 😊

Philip Leth

January 8, 2026

Bro. I just saw a guy on TikTok say ‘generic = bad.’

And he was talking about his blood pressure med.

Like… we’ve got people scared of pills that cost 1/5th the price because Big Pharma told them the brand is ‘safer.’

Meanwhile, the FDA says they’re identical.

So yeah, the system’s broken. But so is the public’s brain.

We need a public education campaign. Not just more data.

Also, why does no one talk about how the brand companies buy up the generic makers? 😅

Angela Goree

January 9, 2026

Enough with the ‘patent thickets’ and ‘authorized generics’-this is why America is falling behind! We let corporations turn medicine into a casino! We have a $2 billion drug that’s supposed to save lives, and instead, we’re playing legal Jenga with patents and loopholes?!

China doesn’t do this. India doesn’t do this. Why do we let our own companies rip off the sick? This isn’t capitalism-it’s corporate feudalism!

And now we’re letting AI predict when people can afford to live? That’s not innovation-that’s surrender!

We need price caps. We need nationalization. We need to burn the Orange Book.

And if you’re still defending this system, you’re part of the problem.

🇺🇸

Tiffany Channell

January 11, 2026

Wow. So after 1,200 words, the takeaway is ‘check the Orange Book’? You spent all this time explaining how complex it is… and then gave a 7-point checklist that any intern could copy-paste from a 2018 slide deck.

And you call this ‘survival strategy’? This isn’t forecasting-it’s basic compliance.

Real analysts track litigation trends in PACER, map patent family trees across jurisdictions, model biosimilar uptake curves using real-world evidence, and simulate authorized generic launch scenarios with Monte Carlo methods.

You didn’t predict anything. You just summarized a Wikipedia page.

And you wonder why models fail?

Because this is what passes for insight now.

Pathetic.

Write a comment