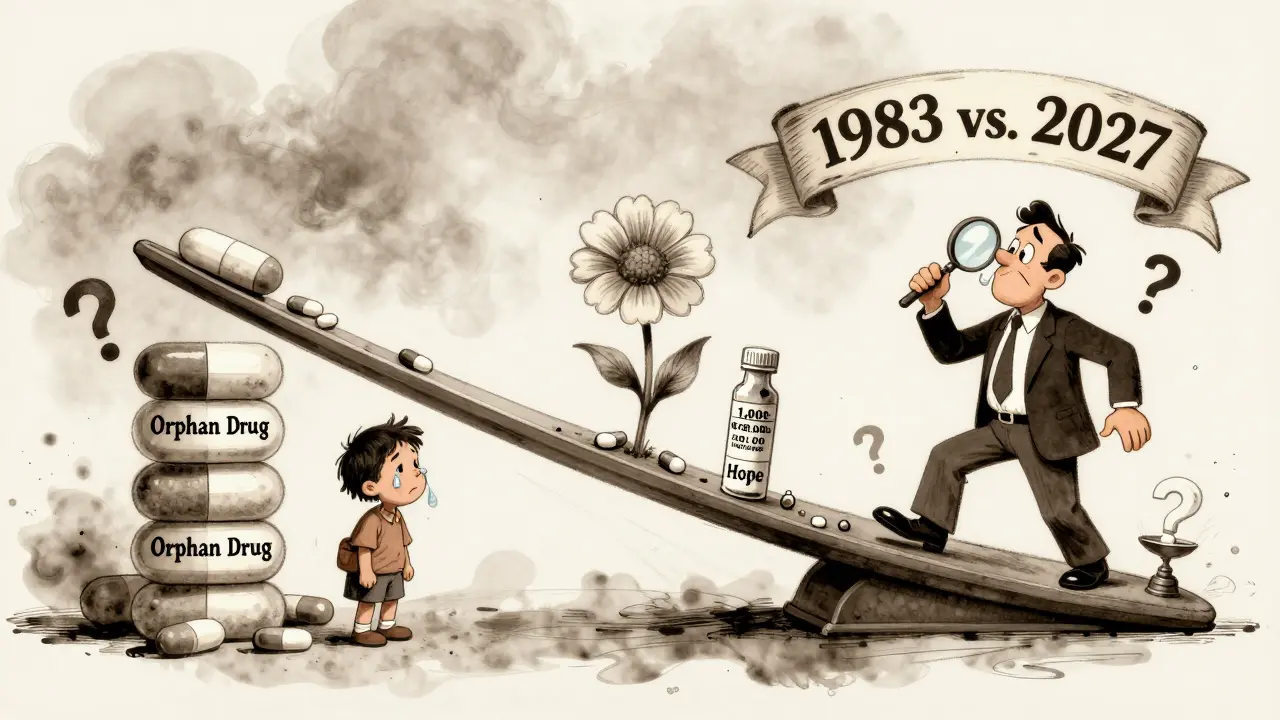

Before 1983, fewer than 10 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, more than 1,000 are approved. The shift didn’t happen by accident. It was forced by a law that changed how drug companies think about profit-and how patients think about hope.

What orphan drug exclusivity really means

Orphan drug exclusivity is a seven-year window where the FDA can’t approve another company’s version of the same drug for the same rare disease. It doesn’t block generics for other uses. It doesn’t stop patents. It only protects one thing: the specific drug for one specific condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

This isn’t a patent. It’s a separate, parallel protection. You can have both. But if your patent expires in five years, the seven-year exclusivity still holds. That’s why some drugs stay protected for longer than their patents. The system was built to fix a broken market. Companies weren’t developing treatments for tiny patient groups because the cost of R&D-often $150 million or more-could never be recovered. The orphan exclusivity rule made it possible to break even.

How the system works in practice

It’s not enough to just say a disease is rare. You have to prove it. Companies submit data showing the condition affects under 200,000 Americans-or that the drug won’t make money even if it works. The FDA reviews this in about 90 days. Approval? 95% of applications get it if the numbers check out.

Here’s where it gets interesting: multiple companies can apply for the same orphan designation. But only the first to get FDA approval gets the seven-year clock. Think of it like a race. Ten teams might be running the same course. Only the winner gets the prize. That’s why biotech startups move fast. They file for orphan status early-sometimes during Phase 1 trials-just to lock in the advantage.

And here’s the catch: if another company comes along later with the same drug for the same disease, they can’t just copy it. They have to prove their version is clinically superior. That means better outcomes, fewer side effects, or a new way to deliver the drug. Since 1983, only three cases have met this bar. The standard is so high, most competitors just give up.

Why this matters more than patents

Most people assume patents are the main shield for drug profits. They’re not. For orphan drugs, exclusivity often matters more. IQVIA found that in 88% of cases, patent protection was the primary barrier to generics-not orphan exclusivity. But here’s the twist: orphan exclusivity still blocks competition even when patents are weak or expired.

Take Humira. It’s a blockbuster drug used for arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease-conditions affecting millions. But the company also got orphan status for rare autoimmune conditions where it’s used off-label. That gave it extra years of protection. Critics call it abuse. Supporters say it’s legal. The FDA hasn’t stopped it.

That’s the tension in the system. It was designed to help patients with no other options. But it’s being used by big pharma to extend profits on drugs that already sell well. The law didn’t anticipate this. It was written for drugs that might never make a dime. Now, some orphan drugs generate billions.

How other countries compare

The U.S. gives seven years. The European Union gives ten. And if a company runs pediatric trials in Europe, they get two more years. That’s a total of 12. The EU also lets them cut exclusivity from ten to six years if the drug becomes wildly profitable-something the U.S. doesn’t do.

Why the difference? Europe’s system is more flexible. It’s designed to balance access and innovation. The U.S. system is simpler: win the race, get the prize. No adjustments. No exceptions. That’s why U.S. companies often rush to file for orphan status here first. It’s predictable. It’s powerful.

But Europe is reconsidering. In late 2023, the European Commission opened a public consultation on possibly reducing the standard period from ten to eight years for drugs that earn more than expected. That’s a direct response to the same criticism the U.S. faces: orphan exclusivity is being used to protect profitable drugs, not just unprofitable ones.

The real cost: pricing and access

Orphan drugs are expensive. The average price for a new orphan drug in the U.S. is over $300,000 per year. Some exceed $1 million. Why? Because the market is small. The company has to recover its costs from just a few thousand patients.

A survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders found that 78% of patient advocacy groups say orphan exclusivity is essential to get new treatments developed. But 42% also worry about pricing. That’s the unspoken trade-off. The system works-but at a price.

Some companies use exclusivity to justify high prices. Others say they have no choice. Without exclusivity, they wouldn’t develop the drug at all. That’s the core argument. And for many families with no other options, it’s a lifeline.

What’s changing now

The number of orphan designations has tripled since 2010. In 2022 alone, the FDA granted 434 new orphan designations. Oncology leads the pack-44% of all approved orphan drugs treat cancer. But neurology, blood disorders, and metabolic diseases are growing fast.

One trend is "salami slicing"-splitting a single drug into multiple orphan indications. A drug approved for one rare disease gets a second designation for a slightly different patient group. Each gets its own seven-year clock. The FDA has started cracking down. In May 2023, they issued new draft guidance to clarify what counts as a "same drug" and when multiple designations are justified.

By 2027, Deloitte predicts 72% of all new FDA-approved drugs will have orphan status. That’s up from 51% in 2018. The system is working too well. It’s becoming the default path for drug development, not just the last resort for rare diseases.

What sponsors need to know

If you’re developing a drug for a small patient group, orphan exclusivity isn’t optional-it’s your business plan. You need to file early. You need to document prevalence carefully. You need to plan for clinical superiority if someone else is close behind.

Most successful companies spend 12 to 18 months building their orphan strategy before they even start Phase 3 trials. They hire regulatory consultants. They run epidemiology studies. They meet with the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development. Ninety-two percent of companies say those meetings are helpful.

The goal isn’t just approval. It’s timing. Get the orphan designation before your patent expires. Get the marketing approval before your competitors. That seven-year window becomes your revenue engine.

Is the system broken?

It’s not broken. It’s working-but not exactly how it was meant to.

It created over 1,000 treatments for conditions that had none. It turned biotech startups into viable businesses. It gave patients real options where there were none.

But it also became a tool for extending monopolies on drugs that could have been affordable. It lets companies charge $500,000 for a pill that treats 5,000 people-while the same drug, for other uses, might cost $10,000.

The answer isn’t to scrap it. It’s to fix it. Maybe require proof of unmet medical need-not just low prevalence. Maybe cap prices for drugs that earn more than $1 billion in orphan sales. Maybe let generics in sooner if the drug is widely used.

For now, the system stands. And for families waiting for a treatment that doesn’t exist yet-it’s the only thing standing between them and hopelessness.

How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts for seven years from the date the FDA approves the drug for its rare disease indication. This protection runs independently of patents and prevents other companies from getting approval for the same drug for the same condition, unless they prove clinical superiority.

Can a drug have both a patent and orphan exclusivity?

Yes. Many orphan drugs have both. Patents protect the chemical structure or method of use, while orphan exclusivity protects the specific use for a rare disease. If a patent expires after five years, the seven-year exclusivity can still block generics for that indication. The two protections work side by side.

What counts as "clinically superior" to bypass orphan exclusivity?

To get approval for the same drug and same rare disease, a competitor must prove their version offers a "substantial therapeutic improvement." That could mean better survival rates, fewer serious side effects, or a new delivery method that improves patient outcomes. Since 1983, only three cases have met this standard-making it extremely difficult to challenge an approved orphan drug.

Why do some orphan drugs cost over $1 million per year?

Because the patient population is tiny-sometimes only a few hundred people in the U.S. The company must recover millions in R&D costs from a very small group. Without exclusivity, no company would invest. The high price isn’t greed-it’s a mathematical necessity under the current system. But critics argue that some drugs are priced too high, especially when they’re repurposed from common disease uses.

Can generic companies make the same drug for a different disease?

Yes. Orphan exclusivity only protects the specific disease the drug was approved for. If a drug is approved for a rare condition but also works for a common one, generics can enter the market for the common use. For example, a drug with orphan status for a rare muscle disorder can still have generic versions sold for other conditions if the patent has expired.

How many orphan drugs have been approved since 1983?

As of October 2023, the FDA has approved 1,085 orphan drugs since the Orphan Drug Act passed in 1983. Before the law, only 38 treatments existed for rare diseases in the entire U.S. The number of orphan designations granted has grown from 127 in 2010 to 434 in 2022, showing how central this pathway has become.

Is orphan exclusivity only for U.S. companies?

No. Any company, anywhere in the world, can apply for orphan designation in the U.S. as long as they meet the FDA’s requirements. Many European and Asian firms file for U.S. orphan status because it’s the most valuable market. The exclusivity applies regardless of where the drug is made.

What’s the difference between orphan designation and orphan approval?

Orphan designation is a status granted early in development, based on the disease being rare and the drug being promising. It doesn’t guarantee approval. Orphan approval happens only after the FDA reviews clinical data and approves the drug for marketing. Exclusivity starts at approval, not designation. Many drugs get designated but never approved.

What comes next?

If you’re a patient or caregiver, know that orphan exclusivity is why new treatments exist. But also know that pricing pressure is real. Advocate for transparency. Ask: Is this drug truly needed for this small group-or is it being used to extend profits?

If you’re in biotech, don’t wait. File for orphan status early. Build your regulatory strategy like a business plan. The clock starts the moment you submit.

If you’re a policymaker, the system is working-but it’s stretched thin. The next step isn’t to eliminate exclusivity. It’s to make sure it doesn’t become a loophole for big profits on drugs that were never meant to be blockbusters.

The law was written for hope. Now, it’s being used to build empires. The challenge is to keep the hope alive-and stop the empire from swallowing it whole.

Comments

Bryan Wolfe

January 12, 2026

This is one of those rare policies that actually worked the way it was supposed to-until it didn’t. I’ve got a cousin with a rare metabolic disorder who got a life-saving drug because of this law. No joke, it’s the only reason she’s alive today. But yeah… seeing the same drug priced at $500K a year while the company makes billions? It’s a gut punch.

Sumit Sharma

January 13, 2026

Orphan drug exclusivity is not a subsidy-it’s a market correction mechanism. The R&D cost for a rare disease therapy averages $1.2B, and the patient pool is often <5,000. Without exclusivity, venture capital would never fund these programs. The pricing is not exploitative-it’s actuarial. If you want affordability, subsidize the patients, not punish innovation.

Christina Widodo

January 14, 2026

Wait, so if a drug is approved for a rare form of leukemia and also works for regular asthma, generics can come out for asthma but not for the leukemia? That’s wild. So the same molecule is legal to copy for one use but not another? That feels like a legal loophole disguised as a policy. How does the FDA even track that?

Prachi Chauhan

January 15, 2026

It’s like giving a lifeline to someone drowning… then charging them $1 million for the rope. I get why the law was made. But now it’s being used to protect drugs that are already rich. A drug for 500 people shouldn’t cost more than a luxury car. The system was meant for hope, not for hedge funds.

Katherine Carlock

January 15, 2026

Can we just admit that the FDA’s 95% approval rate for orphan designations is a little too generous? I read about one company applying for 17 different orphan statuses for the same drug by splitting patient groups by age ranges. It’s like salami slicing but with science. We need stricter definitions-before this becomes the default path for every new drug.

Sona Chandra

January 16, 2026

THEY’RE TURNING HUMAN SUFFERING INTO A FINANCIAL PRODUCT!!! This isn’t medicine-it’s a casino where the house always wins. Patients are being held hostage by corporate greed. I’ve seen families sell homes to afford these drugs. And the FDA? They just hand out exclusivity like candy. This is a national scandal and no one’s talking about it!

Jennifer Phelps

January 17, 2026

So if a patent expires but exclusivity doesn’t the drug stays protected even if it’s been on the market for 10 years? That means a company can basically lock in pricing forever as long as they filed early enough. And no one’s doing anything about it? This is insane

beth cordell

January 17, 2026

Just wanted to say… this system saved my son’s life 🫶 The drug he takes? Cost $350K/year. We had no insurance. We fundraised. We cried. We fought. But without this law? There would’ve been no drug at all. I’m not blind to the pricing problem… but don’t take away the hope. Fix the system, don’t break it. 💔🩹

Write a comment